In 1984 I was living in East London married to a veterinarian. We lived in a small flat over the PeeDee clinic on the ground floor. PeeDee stands for the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, charity-run clinics where London’s poor and unemployed receive free care for their animal companions. Our clients were elderly widows with their even more elderly dogs, gypsies with sick horses, bikers with ailing snakes, and the infamous Mr. Crowder who shared his small council flat with his extended family and around 15 cats.

At 24 I was in my first year of adulthood, having finished two years of college and three years of professional theater training in New York and London. I was auditioning for everything I could find and succeeding to varying degrees, but not to the degree of being paid, in fringe theater productions around London. These were the venues of Thatcher’s England: rooms above pubs that smelled of beer-soaked carpet, church basements that rumbled each time the Northern Line of the Underground passed, echoing civic centre halls. One year we held rehearsals for a Christmas pantomime in a squat (an abandoned house) where one of the actors was staying. I recall the director, who is quite famous now, helping us enter through a window round the side.

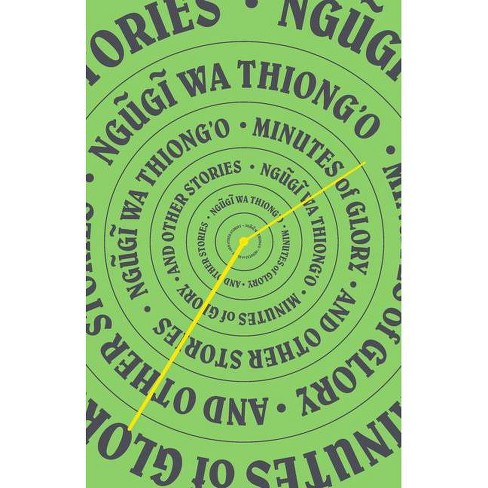

One morning I found an audition notice in ‘The Stage,’ the UK’s weekly theatre newspaper. A play called ‘The Trial of Dedan Kimathi’ was to be performed at the Africa Centre in Covent Garden. The play tells the story of the Mau Mau Rebellion leader, who was executed by the British colonial government in 1957. The call was for actors of all nationalities, but especially those from Africa. Unusually, the notice added that ‘childcare will be provided during all rehearsals for those with children and they will be included in performances.’ It also stated that the play’s co-author, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, would oversee the production personally.

Auditions were held and the Wazalendo Players ’84 were formed, a large ensemble made up of (mainly) English Afro-Caribbean actors in the Kenyan roles, white actors in the English roles, and a charismatic Senegalese actor in the title role. The white actor who played the judge was the only one of us who was actually Kenya-born. This was ironic, but it also drove home to me the reality and recentness of British Colonial history. I was cast in the role of ‘Settler,’ which had been rewritten as ‘Settler’s Widow,’ perhaps due to a shortage of good parts for women in the script, and an amazing South African singing group from Soweto provided the music. Quite a few actresses with small children had gratefully tried out and been cast. One of them was a white South African woman, an anti-apartheid activist, who’d given birth to her oldest in a South African prison where her black husband still languished. At this time, the global anti-apartheid protest movement was reaching its apogee. The Specials hit song Free Nelson Mandela had come out in the spring and it was a moral imperative to play it at every club and party. I was elated. It felt like our production was at the center of the cultural moment. I was eager to learn about a history that my US education had neglected.

V&A Museum archives

During the many weeks of rehearsal, we learned about the history of Kenya, its colonial past, the Mau Mau uprising in the 50’s ultimately leading to Kenya’s independence from the British in 1963. The conduit for this education was our playwright, Ngũgĩ, soft-spoken, always smiling, who graced us with his firsthand knowledge in the form of little anecdotes and contextual explanations pertinent to whatever part of the play we were working on. He himself had recently spent a year behind bars, imprisoned by the Nationalist Kenyan government, in the same prison where Dedan Kimathi was held, decades earlier, by the British. His most recent novel was written on toilet paper in his cell. Now living in exile in London, his writing, while absolutely anti-colonial and Marxist, also continued to expose the corruption of the current Kenyan government (he jokingly referred to them as the ‘WaBenzi tribe’ due to their penchant for owning fleets of Mercedes Benz). I came to understand the play we were doing as not just an historical agit-prop account of Kenya’s martyred hero, but also a sly commentary on the present Kenyan rulers and their ongoing oppression of free expression and human rights. This double sense of the play was acknowledged in rehearsal, to be sure. Once, spending time in the creche with the mothers and children, the lead actress, who had recently finished her degree at university, explained to us that these “native neo-colonialists” were only duplicating the system of oppression they had been taught; as before the Europeans arrived the entire continent of Africa had been composed of peaceful matriarchal societies. This didn’t sound one hundred percent right to me, but I lacked information to counter.

We formed a tight, chaotic bunch (I am still in contact with one of the mothers: she’s now a grandmother of four) and rehearsals were rambunctious and creative–credit that to our director, Dan Baron Cohen–and the final production was sold out every night, which was probably due to the fact that the Kenyan government accused us of being paid by the Soviet Communist Party and lobbied the British government unsuccessfully to halt the production. You can’t buy that kind of publicity!

Lower right, Jenette’s foot and calf.

I had one big monologue in the show, which I had well prepared on the day we first ran the scene. A defiant Dedan Kimathi is held in chains in the dock, the whites and blacks on either side. As the scene progresses, the judge is unable to subdue the eloquent prisoner who gives a fiery speech about the injustices of Colonialism and Capitalism. My character, the Settler’s Widow, leaps up in a rage and takes the court hostage, threatening to shoot Kimathi. In a racially charged counter-narrative she describes the murder of her husband and daughter and the burning of their farm by the rebels. “I am a worker! ” she cries. “I came to this country as a wife of a soldier. A simple soldier. Fighting against banks, mortgages, the colonial office, the whole lot on my back!” I’m pretty sure I nailed it, because afterwards the actor playing the lead went to Ngũgĩ and Dan to complain that I was coming off as too sympathetic (pro tip: never comment on another actor’s work). Ngũgĩ very gently told him that he understood his concern, but that “the interpretation is correct. These were real people. Everybody has a story to tell.”

That was forty years ago. In looking up these images and details I discovered that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o left London a year after I did, and is now a Distinguished Professor at University of California Irvine, an hour south of my house.